Learning a new skill, finishing a book, launching a new company, and losing weight all appear to be a random assortment of activities. Upon closer inspection, you’ll discover that they are alike in one fundamental way.

They are all task-oriented goals.

Many people set goals for themselves, and while some will reach those targets, most do not.

Our job as designers is to shift this dynamic into the favor of users, customers, and the communities we serve.

There are a variety of reasons why people will fail to reach their goal, but among the most common is the inability to construct or find a path to the desired target.

Imagine the mental processing power that would be required if you were challenged to wake up tomorrow morning and map out each step of your day before you began. The cognitive ability required would deter most from starting, and those who did would likely find themselves distracted easily. That’s because mapping out a day of individual steps requires intense focus.

So, rather than embarking on such foolish activities that would keep most of us from beginning our day, we break our morning tasks down into small, repeatable tasks. Most of the time, we don’t even think about the steps involved because we’ve done them so often successfully.

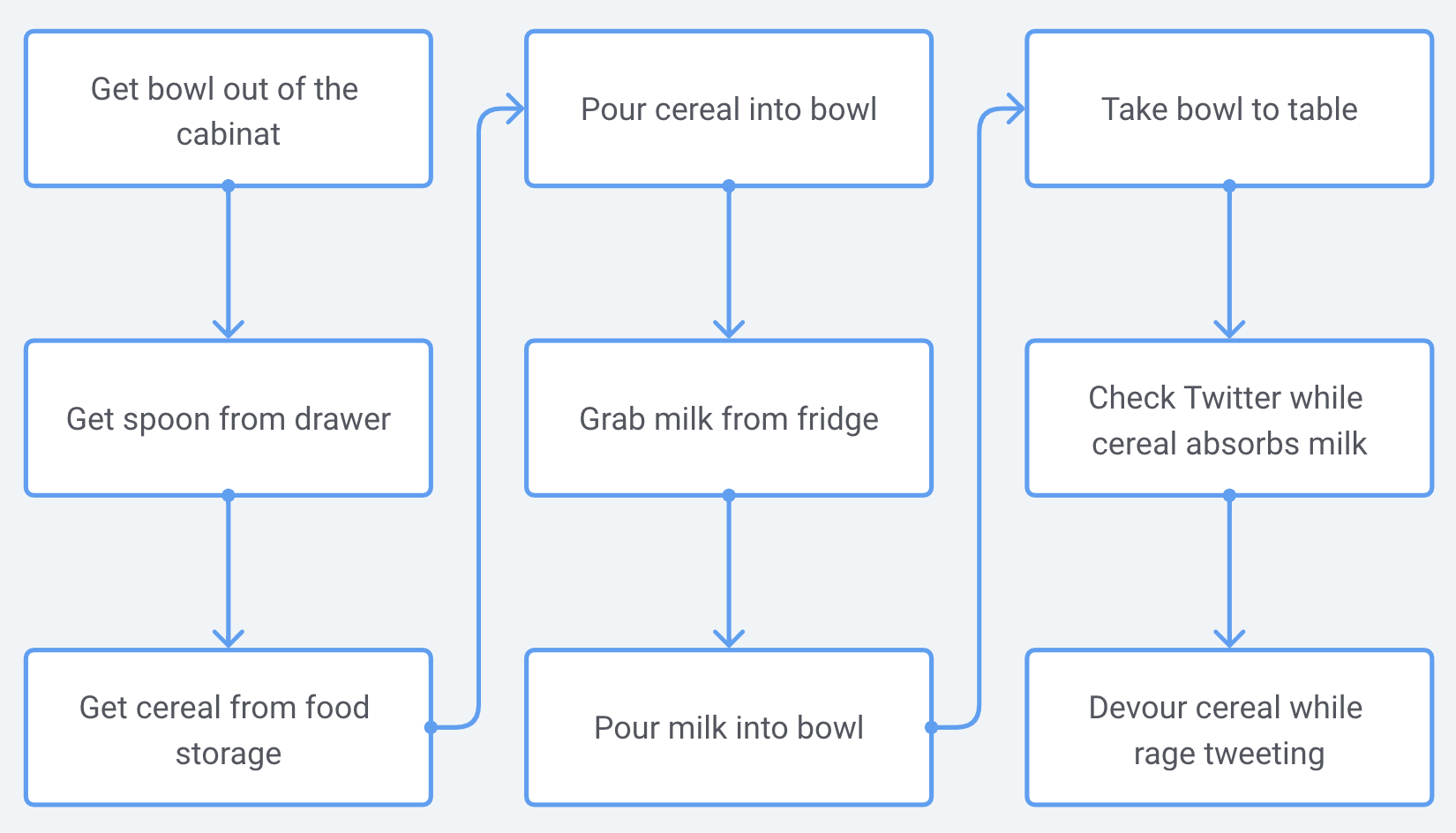

As an exercise, I’ve mapped out my morning breakfast ritual into a short series of steps.

Source: newpragmatic.com

Source: newpragmatic.com

When my daughter prepares a bowl of cereal, the same routine runs (minus the rage tweeting), and she eats a bowl of cereal. However, it becomes clear that there are some steps that I perform but have failed to list occur when she makes a bowl of cereal.

- Leaving the cereal box on the counter.

- Leaving an empty bowl on the table.

My inability to initially see the entire task illustrates how blind spots can work their way into our understanding of the stories we are attempting to map out.

To guard against this tendency, we’re going to use a three-step process as we map out user stories. Each step ensures we’re doing our best to help the user reach their goal while also uncovering our blind spots.

Creating pathways

Whether you hear it referred to as a path, flow, or map the job of getting a user from A-to-B requires equal parts of imagination, interrogation, and iteration.

Imagine the narrative path

When trying to guide the user to their goal, you’ll likely create a process that doesn’t currently exist. We do this by telling simple stories about the steps involved in reaching that goal. This approach allows us to marry the task user is attempting with our knowledge of the system — even in systems that don’t exist yet.

While your competitive research may have surfaced similar structures in other products, you should use that knowledge only to inform the path you are creating.

In the affinity mapping chapter, we grouped tasks for a pet grooming shop. I used that work to provide the background needed for the example path below, which allows pet groomers to notify customers when their pet is ready to be picked up.

Source: newpragmatic.com

Source: newpragmatic.com

The path that I created is imaginary. It is a story filled with informed assumptions. It likely has missing components. It may require additional work on other parts of the system to be functional, but we’ve created the first attempt.

Interrogate the path

When tasked with creating a path from scratch, you’ve likely missed some essential steps. Such is the case with the example above. I failed to consider the possible variables that could be present in this system. Those variables include:

- The type of device the attendant might be using.

- Does the owner have a contact preference?

- What to do if the owner dropped off multiple pets.

Each of these variables forces further examination of other aspects along our proposed path. On some items, like information regarding the attendant, we may have existing research that could inform the initial steps. Other elements, like those regarding the owner, might be interface refinements to streamline the process.

Regardless, it’s essential to be both proactive in seeking out flaws in the original path and be welcoming of feedback on your work. Accepting that the work likely has flaws is an easy way to remove the ego from the situation.

Iterate, iterate, iterate

I like to begin this process with sketching because I feel significantly less invested in a sketch. If you remember the introduction to ‘‘drawing toast’’ from Systems Thinking, you’ll recall that using sticky notes for the individual nodes of a system also reduces friction to change. Everything that we can do to lower perceived investment makes it easier for us to update those initial versions.

When you initially begin charting a path for users to follow, it will rarely feel intuitive, but as we refine these options, our path becomes smoother. Because we’ve had time to consider the possible options, we make improvements where needed, and it’s in these refinements that our paths transform into user flows.

It is important to remember that we’re iterating to increase the likelihood of task completion. We may discover along the way that to achieve a goal, we need to break our tasks down further. Unlike the complexity we sought in the models built when thinking about how systems operate, here simplicity reigns supreme. Our goal is to assist the user - even if that makes our job harder.

While the flows may still require further work interrogation and iteration has them far closer to the target than their original form.

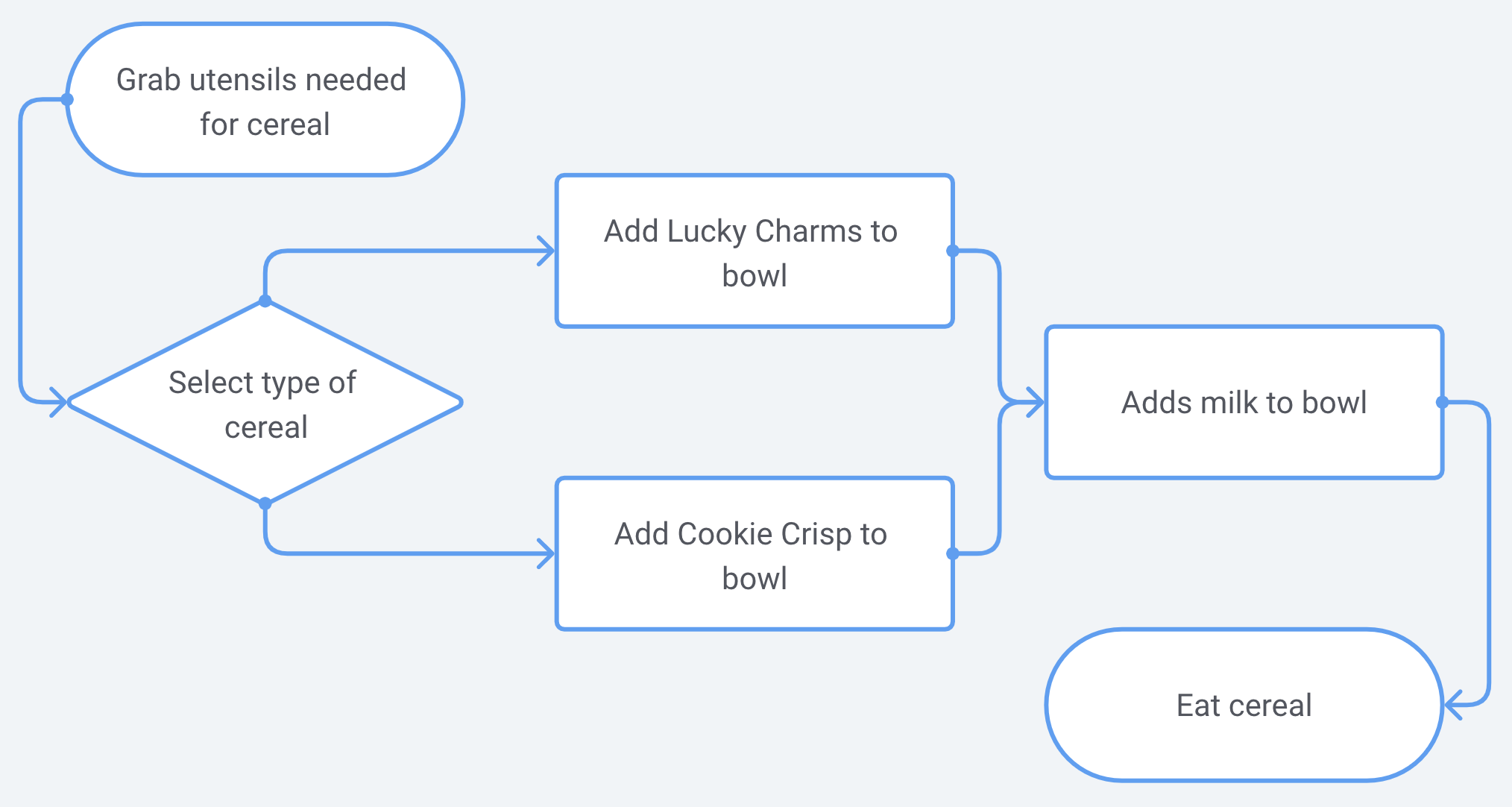

User flow components

When we begin creating our pathways, it is very logical to use the box-and-arrow model to indicate a step and the direction the flow will take. As our work grows more complicated, it needs to adapt to display the type of action taken. To do that, we begin layering logic into our work to make it easy to understand where decisions could change the course of our diagrams.

The visual enhancements you could apply to your work begin with elementary shapes and graduate up to diagrams with completed designs.

The shapes

The most common user flows diagrams are those that include a variety of shapes. These simple shapes help define what is happening along the displayed path.

Four basic shapes are present in all use flows. The oval, rectangle, arrow, and diamond all carry specific meaning to help your teammates quickly decode the flow they are studying.

| Shape | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Oval | Beginning or ending of a flow |

| Rectangle | Single step in the process |

| Arrow | Intended direction between pieces of the diagram |

| Diamond | Decision to be made in the flow |

Alternative forms

It should come as no surprise that all user flows aren’t just a collection of shapes connected with arrows.

Of the different options available most are just variations that gradually increase in detail. I find connecting wireframes together to be useful, but anything past that level of detail is just creating documentation that’s too hard to keep updated.

One alternative that goes a different direction is UI Flows, a style created by the team at Basecamp.

At its core, the goal of UI Flows is to quickly link the interface view with the action that occurs — without adding a lot of documentation overhead.

While you won’t likely begin your path-building with UI Flows, you could certainly put them to use in later iterations of your flows.

A world of our own making

With every user flow that we create, we are detailing out a particular part of a more extensive system. This is an inward-focused version of a journey we’ve already taken together.

In the chapter on System Thinking, we focused on how our overall products would interact with other systems that they encounter that are not under our control. Now we have shifted our focus to creating numerous small systems that are mainly under the control of our team.

Previously, we wanted to understand how those systems interacted so that we could mitigate adverse outcomes on society at large. Now, you want to be aware of how your internal systems interact to avoid negative impacts on your team.

The awareness that we were cultivating to be good community members before is now being refocused to make us better teammates.